Take Me Where I’ve Never Been

📅 August 2008

►ᴛᴡ ғᴏʀ ᴄʜɪʟᴅ ᴀʙᴜsᴇ ᴀs ᴡᴇʟʟ ᴀs ʙʀɪᴇғ ᴍᴇɴᴛɪᴏɴs ᴏғ ᴅᴇᴀᴛʜ, sᴜɪᴄɪᴅᴇ, ᴀɴᴅ ᴅʀᴜɢs◄

For Anthony’s entire life, it had been his older brother that made it all bearable. However fragile the bearability, Hunter had been the one to keep it up, with his gentle eyes and sense of humor and the fact that he’d throw himself between Anthony and their father when the belt came out. Or fists. And he’d take whatever he was allowed to take in his little brother’s or his mother’s stead.

Anthony had missed him horribly when he’d first left for the military, with his promises of paychecks and eventual escape from their father’s violence—but the ache Anthony had felt then was nothing compared to the agony now, knowing his older brother was never coming home.

In the months since Hunter’s death, to Anthony, it seemed the world had gone grey. Even as his father’s rage-drinking worsened in the aftermath of his eldest son’s funeral, even as that rage was taken out on Anthony with ever-increasing severity...the grief-haze in his head kept him somehow “othered” from it all. From the nights his back went numb with pain; from how routine it became to be breathing in the smell of bloodied leather. The evenings onward from May bled together like the welts on his back did, somehow landing him in early August, on another night of dully letting his intoxicated father yell and curse and work himself up to violence.

“Go get the damn belt.”

Anthony heard his father’s words but couldn’t process them; even after almost three months the heavy fog of grief refused to leave his head, and he felt stupid and detached. In dreamlike slow-motion he watched uncomprehendingly as his father’s alcohol-reddened face contorted furiously at the apparent refusal to comply—but Anthony’s brain stubbornly refused to catch up and he continued to just stare dumbly, even as his dad smashed the empty whiskey bottle in his hand against the countertop. Both the sound of shattering glass and his mother’s cry of fear reached Anthony’s ears as if heard through water or thick glass, all noise distorted by the same sluggish haze through which he watched his father raise the broken bottle in preparation to swing.

Reality finally kicked in and snapped back to its true speed for him just before the jagged glass edge of the bottle cut into his neck.

There was no time to move out of the way, to dodge—it was too late to do anything more than twist his head and shut his eyes out of instinct as the bottle carved up from just below his jaw, across his cheek, over his eyebrow—just barely missing his left eye.

An adolescence of being punished for flinching or pained screams couldn’t keep Anthony from crying out this time; it was pain unlike any pain before it; sharper and colder than any belt lash or punch, and so intertwined with fear that the two were indistinguishable. Pure terror gripped him as blood flooded down his face, rendering him half-blind. His heart was pounding in his ears as he stared in shock at his father, who stood with the bottle still raised, eyes still angry.

It was in that microsecond of noting the lack of hesitation or regret on his father’s face that something snapped. Anthony wasn’t waiting for his brother’s arrival back home anymore; wasn’t tethered to his father’s house by anything other than fear and habit. And suddenly the fear of staying outweighed the fear of running, because blood was soaking Anthony’s shirt but his dad still looked like he might swing again. The ground beneath their feet seemed to shift, there, in the fight-or-flight moment where his father lost all parental authority and became nothing more than an opponent in a fight for survival.

His dad had stood up with drunken aggression, and in doing so, pushed the metal counter stool he’d been sitting on out and away from himself—closer to Anthony. With nothing else in arm’s reach and only a split second to act, Anthony made the decision. Fear and adrenaline coursing through his bloodstream, he went for the stool faster than his drunk father could react, then spun on his heel as he half-swung, half-threw it into the older man’s ribs. Drunk and caught off-guard, his dad lost his balance and was forced to catch himself on the countertop—and Anthony took his opportunity to bolt; he sprinted past his father, wrenched open the front door, and without looking back, vanished into the late August evening with nothing but the clothes on his back and his brother’s dog-tags around his neck.

He ran until he no longer could; until his legs began to seize up and his lungs burned with the taste of copper. He’d been all fear and no direction and terror drove him away from the front stoop lights of the unfamiliar neighborhood around him—anyone behind those doors would surely return him to his father’s hands—so he shied away from where he might be spotted, stumbled off the street and into a drainage ditch. There was a cement culvert under the road, and since Fresno was bone-dry in August, Anthony took refuge in it; curled up and hugged his knees to his chest so tightly he could feel his heartbeat against them. His adrenaline was still pumping and his heart was pounding hard, harder than ever before, working overtime to pulse blood through his body—and, he realized, from the wound in his neck. Anthony pressed his hand against the cut, his mind racing.

I’m bleeding to death. I’m dying. I’m going to die, he thought to himself, panicked and half-blinded by the blood running down his face and over the hand he tried to staunch the flow with. His shirt was already wet with it; a dark, palm-sized stain had bloomed at the collar and was threatening to grow, even as he fought to apply pressure. There, sitting down in the quiet dark, breaths coming quick and shallow, with a palm pressed to his neck as he waited for the bleeding to stop, the adrenaline Anthony had been relying on eventually began to wear off—and the fatigue of the shock and the stress, of sprinting so far and losing however much blood, finally caught up. Lightheaded and scared, Anthony struggled against the slow, incessant pull toward unconsciousness.

I’m actually dying, he thought desperately, too tired to cry and failing to keep his eyes open, Is anyone even gonna find my body here...? I just want my brother…

His last coherent thought before he could no longer fight his head’s slump to his shoulder was a half-hopeless, Maybe that’s what I’m getting.

It was still dark when Anthony woke up, and he felt supremely disoriented as he pushed himself up into a sitting position, slightly chilled from laying on the cool cement despite the warm summer night.

I’m not dead? he thought to himself, confused. As if in search of proof, he blearily groped his way out of the culvert. The dark tunnel gave way to the dry ditch and the sky overhead—which was just barely beginning to lighten in hue at the very edge of the horizon—and Anthony took a moment to just sit back on his heels, knees in the dirt, and stare up at it.

Holy shit, I’m not dead, he thought, then; ...So now what?

Still kneeling on the ground, he bent his head and pressed his cool palms to his eyes, feeling overwhelmed. The contact made the scabbed cut over his left eye ache sharply, and the pain combined with the scaly texture of the dried blood on his skin brought the reality of his situation to reluctant light. The image of his father standing in front of him, arm raised and bottle in hand, was burned into Anthony’s mind—and if he was sure of anything at all, it was that he was never, ever, returning to that house again. Having that much certainty did him no favors, though; he was still a fourteen-year-old runaway; alone, with an obvious injury, a bloodstained shirt, nowhere to go, and no way to get there anyway.

He suddenly felt indescribably lost, kneeling with his head in his hands in the darkness of an unfamiliar neighborhood, and he swallowed hard against the painful lump forming in his throat. Then, somewhere in the distance, a train whistled. Coherent thought didn’t catch up immediately—he just raised his head, which felt somewhat clearer, and tried to figure out which direction the sound was coming from. It felt inexplicably important, and he quickly got to his feet and scrambled out of the drainage ditch, up to the street—straining to hear, to face the direction of the train tracks. As the sound died and he looked down the road in its wake, the first thought he had was so obvious it made him want to laugh. ‘Trains go places...’ But that was the root of it, simplistic as it sounded: Trains went places, went fast and far away; out of Fresno, out of California, out of his father’s reach. Somewhere along the distant railroad tracks, past the tangled mess of suburbia, was his escape route.

Getting there was anything but easy, though. Anthony pointed himself in the general direction and started walking, but the cover of darkness only lasted a couple hours, during which he only heard the train whistle once more—just one opportunity to correct his course before dawn. The journey was nerve-wracking at best once the sun rose. Trains only seemed to sound once every hour and a half or so—if Anthony felt uncertain of his course, he was forced to find a copse of trees or another culvert to hide in until he could hear the train whistle and re-orient himself. It was easy to get lost or turned around and more than once he found himself facing in the exact wrong direction, unknowingly undoing his own progress. As the sun climbed higher in the sky, Fresno’s summer heat set in, unforgiving—but as he walked Anthony didn’t dare take off his shirt and expose his belt-scarred back. He was already riddled with anxiety, keeping his head down and counting on those around him being too self-absorbed to look closer; hoping against hope that he was tall enough to avoid arousing suspicion from concerned adults but short enough to fly under the radar and keep his injury out of view. Hour after hour passed like that, in hypervigilant cycles of walking, hiding, waiting on the train to sound again so that he could walk some more. During the sitting and waiting, his destination slowly took shape in his mind. When he was younger, his mother had talked to him and Hunter about what she’d expected America to be like when she was younger, before crossing the ocean to marry Anthony’s father. It was the iconic Times Square that really took her in; the ball drop, the famous photograph of the sailor kissing a stranger. Then the skyline, the Empire State building, Central Park. She talked about bright lights and endless culture, about a city pulsing with life and opportunity. A city where it snowed. A city she’d never been to.

Walking through the sprawl of a city he felt nothing for other than a desire to leave, Anthony set his goal on his mother’s utopia: He wanted to get to New York City. But he’d been awake for sunrise and as the sun started to fall from it’s midday height, Anthony started to feel hopeless despite having a more solid goal. It seemed endless, infinite, like he was walking on a suburban hamster wheel with no way to really reach his destination. His legs were aching and threatening to seize up when suddenly the train whistle sounded again. This time Anthony felt the vibrations in the ground as it approached; realized the tracks must just be a block or so away, just across this intersection, just past these next few buildings—he broke into a run, desperate to see, and discovered he’d made it, somehow, not just to the train tracks—but to the Fresno freight yard itself.

There was a pile of scrap lumber near the edge of the yard, half-obscured by some stunted shrubs that made it feel concealed enough from the possibility of suspicious eyes to be safe for Anthony to sit down and gather his thoughts on. As he sat, though, the weight of the past 18 hours finally caught up—and doubt and anxiety washed over him in waves. He was fourteen. He was hungry and thirsty and scared of being caught or even seen. In theory, train-hopping was like the movies; just wait for dark and sneak into a boxcar and get wherever you’re going. But there seemed to be a million train cars and a dozen tracks, and he didn’t know where any of them were going or when or what he was doing at all. Feeling indescribably lost but out of his father’s house, with no hand nearby to be raised in retribution for it, Anthony let himself to do something he’d been disallowed through threat and punishment for the past fourteen years: He cried.

It was only for a few minutes and the salt stung the cut on his face, but it was cathartic all the same; clutching Hunter’s dog-tags, Anthony finally mourned his brother, mourned the childhood they both should have had, mourned leaving a house that never managed to be a home—and finally didn’t have his father’s voice from overhead, commanding him to straighten up, to shut up, to “Stop crying like a pussy, boy,” or “Suck it up and act like a man.” And when the sobs stopped coming and his tear-tracks dried, and Anthony did find the strength to straighten his spine and square his shoulders, he knew it was with his own strength, on his own terms. He glanced at where the sun sat in the late-afternoon summer sky and took a deep, shaky breath.

“Hey!”

Anthony twisted around at the greeting with a start, anxiety flooding his body and tensing his shoulders despite the voice’s jubilant tone. Upon turning around, he saw the owner of said voice was another boy; about Anthony’s own height but slightly slimmer, with jet black hair that almost reached his shoulders and a smile that seemed just a bit too wide for his face—though the grin dissolved into a look of shocked concern when Anthony faced him.

“Oh jeez, dude, you alright? What happened?” the other kid asked, quickly recovering from a barely noticeable balk and walking closer.

“I’m fine,” Anthony said quickly, warily, feeling flighty and distrustful of someone who had no fear of approaching a stranger whose face was half-covered in dried blood.

“Oh, good! But you should wash that off anyway,” the other boy replied easily, his smile returning as he let the strap of the backpack he had slung over one shoulder drop to his elbow so he could reach in.

“Catch!”

It was more out of luck than skill that Anthony caught the bottle of water that the black-haired boy tossed to him, but the catch was met with bright eyes and that toothy, tilted grin—and, finally, an introduction:

“I’m Cheyenne. Well, technically Kaspar, but—Cheyenne. Or ‘Chey’! I wanna try out ‘Chey,’” Cheyenne/Chey/Technically-Kaspar said, his excited smile not faltering in the slightest, despite the fact that Anthony was sure he was staring at the other boy as if he was nuts. Because clearly he was absolutely insane; Anthony hadn’t expected to run into someone with fewer social skills than he himself had, but Cheyenne (Chey?) talked just a little too fast and stood just a little too close and seemed devoid of the common sense to not just walk right up to random strangers.

...But the bottle of water now in Anthony’s hands was full and unopened, and Cheyenne’s smile was bright and friendly and expectant and he rocked back and forth on his feet like a little kid too excited to keep still. It was difficult not to trust him.

“...I’m Anthony,” Anthony said, twisting the cap off of the bottle of water with a snap, “Uh. Thanks, Ch...uh. Cheyenne?” He stumbled over the inexplicable hard “ch” of ‘Chey’ and the fact that he’d been given three potential names that sounded nothing alike, but Cheyenne didn’t seem at all put off.

“Cheyenne or Chey, yeah!” he responded with a half-shrug and wide smile, then laughed, “Your name is Anthony? You don’t look like one at all!”

If there was a way to say something questionable but sound the opposite of rude while doing so, Cheyenne seemed to have found it—and even though smiling was unfamiliar and hurt when it stretched the cut on his cheek, Anthony found himself unable to resist the impulse.

“What do I look like, then?” he asked, splashing some water into his left hand to try and wash the blood from his face, “And where are you “trying out” ‘Chey’ from? It doesn’t sound anything like Cheyenne or Kaspar.”

Cheyenne (?Chey?) leaned back on his heels and gave Anthony a grinned once-over.

“I dunno! You could be a Matt? Definitely not Anthony, though,” he half-laughed, “and Chey’s just the first four letters of Cheyenne, it’s not from anywhere.”

“‘Matt’? Pff, what? No way,” Anthony half-snorted, “And I mean—okay, fair enough about the spelling, but you’re saying it like—”

“Do I seem like someone who should go by the nickname ‘Shy’?” Chey interrupted, then immediately laughed at his own joking rhetorical question. It was genuine laughter, warm and light and almost contagious; Cheyenne seemed half-magical in some way, like he was just a bit too pure and smiled a little too brightly to actually be real. But he seemed to be.

“And we’ll figure out a name for you, don’t worry,” he shrugged smilingly at Anthony—who raised an eyebrow but felt strangely safe in his presence, despite the past 18 hours and the blood he was washing from his face.

“Where are you headed, by the way? I’m assuming you’re not just sitting around outside a railyard for the peace and quiet,” Chey said, sitting down on the scrap lumber beside Anthony, “So, are you catching out of Cali, too?”

Anthony hesitated only momentarily. “...Yeah. I wanna get to New York City,” he said, not knowing how possible it was, or if maybe he was about to get laughed at. He wasn’t expecting the way Chey’s eyes lit up, the way his already-brilliant smile grew even brighter.

“No fuckin’ way!” Chey positively beamed, “I’m heading back to New York City! What are the chances?! We can travel together!”

“Heading back?” Anthony asked, struggling to divide his attention between washing his face, listening to Chey, and figuring out what to do—though it seemed like the last two could now be combined.

“Yeah, I usually work in the city! Just had a thing out here,” Chey said, practically vibrating with excitement, “Whaddya think? It makes sense, right? Travel buddies?”

There was really no denying it; Anthony knew he was totally out of his depth, but Chey seemed experienced and self-assured and eager. It was a no-brainer.

“...No, yeah, you’re right,” Anthony said slowly, “it’s a good idea.” He offered Chey a tentative smile. “‘Travel buddies’?”

“Hell yeah!” Chey responded, punching the air in triumph and tossing his head like an over-excited horse, his grin ecstatic and his eyes impossibly bright. He seemed to catch and contain himself slightly though; his expression softened in some way, became more gentle than overwhelmingly exuberant as he leaned forward slightly to look at Anthony’s face.

“You’ve got most of that blood off. Missed a spot on your neck, though. What happened to you, man?” Chey asked, the question still loaded enough to make Anthony tense up, but rendered non-threatening by the kindness in Chey’s eyes and the fact that sympathy outweighed curiosity in his tone.

Anthony sighed uncomfortably and averted his eyes—but answered.

“My dad,” he said bitterly, unable to keep himself from instinctively tensing at the mere thought of his father, “My dad happened.”

“Your dad did that to you?!” Chey gasped, his eyes wide with dismay, “Some of the guys flying signs closer to downtown seemed weirdly aggro about their street corners, I thought maybe you had a run-in with one of them…”

Anthony shook his head. “Nope. Just my piss-drunk father.” He ground his teeth briefly. “Whatever, though. I’m done with taking his shit. I’m gone.”

Chey frowned but nodded, the gesture unmistakable as solidarity.

“You’re free,” he affirmed, then looked away and shook his head, sat up straighter. “Dunno, but…My foster mom mighta been like your dad? Took her shit out on us kids. I left, like you. And for what it’s worth, I don’t think about her anymore. I’ve got this life now. It’s mine,” he said firmly, as though impressing the words not only on Anthony, but on himself as well.

“Is she the one who did that to your neck?” Anthony asked, gesturing with his thumb. When Chey had shaken his head as he sat up straight, his long black hair had stopped concealing a pink scar that stretched across the left side of his throat, a little below his jawline. There was a brief pause where Chey froze, and Anthony looked up curiously from the scar to meet Chey’s eyes.

“She...No, not exactly. It’s uh, a rope burn scar,” Chey said finally, hesitating for the first time, looking somewhat anxious, “I tried to kill myself a couple years ago.”

“What? Why?” Anthony asked, tilting his head uncomprehendingly, baffled by the disconnect between the answer and Chey’s previous aura of endless optimism.

It was painful, in the wake of Anthony’s question, the way Chey’s demeanor changed; the way his face crumpled. His bright smile had already vanished, but now his seafoam-green eyes changed tide and grew dark and guarded and scared. He looked down and away and his hand jumped to cover the scar on his neck as his shoulders hunched heartbreakingly inward.

“I just—something bad happened to me. I really don’t wanna talk about it,” he said, his voice wavering, “I’m sorry, I just can’t...”

Anthony knew the two of them had just barely met, that any impression he’d gotten of Chey’s character could be a total misinterpretation—but there was something that felt intrinsically wrong about seeing the boy with a blinding smile hunched over and sad and scared.

“Don’t—Don’t fuck yourself up over it, man, I don’t need to know. Sorry,” Anthony said, hesitating only briefly before somewhat awkwardly resting his hand on Chey’s shoulder in a gesture of comfort. He didn’t know exactly what to do; Hunter had always comforted him with protective hugs, squeezed shoulders, ruffled hair and kind words. But they’d been brothers and Chey was a stranger and Anthony didn’t know where the boundaries were. Maybe Chey didn’t, either, though; he leaned into the touch rather than pulling away, seemed reassured rather than made uncomfortable.

“I’ll get there,” Chey said suddenly, with a determined shake of his head, “I swear. I’m not hiding anything, I just…I get all messed up when I think about that house too long.” He squared his shoulders and sat up straight again, and though the action was clearly forced, he seemed to draw some reassurance from it.

“I’m okay now,” he said firmly, more to himself than to Anthony, “I’m safe and I don’t need to freak out. I’m almost fourteen. I’m okay.”

“Almost fourteen?” Anthony asked, so taken aback he forgot to continue to try and be clumsily comforting, “You’re younger than me?”

Chey smiled amusedly at his tone and quirked an eyebrow, rapidly recovering from his brief foray into his apparently painful past.

“It can’t be by much, can it?” he replied, “I turn fourteen in October. How old are you?”

“I turned fourteen in May,” Anthony said, “So, no, it’s not by a lot, but you—you seem to know what you’re doing, and you have a lip ring, and you mentioned working…” He felt supremely confused but Chey just shrugged smilingly.

“Yeah, it’s a weird line of work though—I’ll tell you about it at some point. I pierced my lip with a safety pin when I was twelve. And as for knowing what we’re doing…I guess I have some idea.” Chey laughed and bent over to retrieve something—a rather battered North American railroad atlas—from his backpack. It was big; had been halfway rolled-up just to fit in the pack, and when opened it fell across Anthony’s lap as well as Chey’s, who scooted closer as he flipped to the page spread for California.

“So. Game plan,” Chey said, pointing out Fresno’s little black dot on the map and tracing a line running through it, “It’s hot, it’s summer. I’m not crazy about the idea of running south and getting cooked alive in a train car down in New Mexico, and we can’t head straight east because of the mountains.” He pointed to the Sierra Nevadas, then moved his finger back to Fresno, ran it upward as he continued, “Our best bet is to get on with Union Pacific—that’s this solid black line here—and head north. We might be able to switch trains and start heading east in Roseville or Marysville, but we could go all the way to Oregon.”

Chey pointed at the locations he mentioned, cross-checked with a company map for Union Pacific near the back of the atlas, then found Oregon’s page spread. “If we do that, we can switch trains in Chemult or Portland—Portland’s supposed to be really busy, though.” He turned back to the company-specific maps and flipped through a couple pages, apparently able to make much more sense of the squiggly lines and ‘tonnage’ keys than Anthony could. After a couple moments, Chey nodded with silent understanding and looked up again.

“We’ll catch a CSX train out of Chicago once we get there, and that’s how we’ll get to New York City,” he said, “Sound good?”

“Sure, yeah,” Anthony said with a bemused nod and a shrug, “Whatever you say, honestly. I’ve never hopped a train before. Hell...I’ve never left California before.”

Chey’s eyes widened and he tilted his head.

“Really? Never?” he asked, seemingly astonished, then returned to his usual grin. “Well, I’ve never been this far west, so it’ll be an adventure for both of us, then! We’ll get to see so much!” He seemed genuinely excited, his eyes bright and smile lingering as he packed up his railroad atlas.

“We’ll have to wait until dark to catch out,” he said, looking out into the railyard, “so it’s gonna be a few hours. We should find a shadier spot, I’m dying. C’mon.” He stood up and looked expectantly at Anthony, who hesitated only for a microsecond. Yeah, maybe Chey was nuts, maybe he was over-friendly, maybe he was a total stranger—but there was something in his eyes and smile that spelled out trustworthiness, so Anthony nodded. Returned Chey’s smile. And followed him.

They found a shadier, more secluded spot just a short distance down the tracks, still allowing them a view of the yard—just finally letting them escape from being at the total mercy of the sun. They passed time playing tic-tac-toe and hangman with a stick in the sandy dirt, flipping through Chey’s railroad atlas and laughing at city names (and Chey’s insistence on pronouncing ‘Pisgah’ as ‘Piss-gaw’), or just idly talking. When Anthony mentioned how long he’d spent walking that day, Chey pressed another bottle of water on him, insistent and concerned.

“I don’t want to take more of your water—” Anthony said hesitantly, but Chey waved him off.

“It’s our water,” he said firmly, “Travel buddies, remember? Besides, I can buy more. I’m okay for cash right now.”

“...Thanks,” Anthony replied, then took a long drink before deciding to ask, his curiosity rekindled by the comment about cash; “What kind of work do you do, Chey? How are you earning money? You said it was weird.”

Chey leaned back against his backpack and looked up at where the dying rays of sunlight filtered through the scraggly branches overhead.

“You’re not allowed to judge me,” he said finally, glancing at Anthony out of the corner of his eye, “Like, just…sometimes you gotta do stuff, right?”

Anthony felt unsettled, but nodded anyway. Hunter hadn’t joined the military because it matched with his values, after all—sometimes people just did what they felt was their best option.

“...I run drugs,” Chey said with something akin to an apologetic grimace, “It’s not like I deal ‘em or take ‘em or anything, though! I’m not a junkie. I just have a boss who sets everything up and I…do the deliveries. Cops don’t tend to think kids are gonna have a couple kilos of coke in their backpacks. It works out.”

“Oh,” Anthony responded, feeling strangely underwhelmed, “I thought maybe you were the world’s youngest hitman-for-hire or something.”

Chey laughed and looked at Anthony, smiling almost disbelievingly.

“It doesn’t freak you out?”

“I dunno,” Anthony shrugged and felt that when it came to choosing company, between his father and Chey? Chey was preferable by far—questionable employment or not. “I mean…You’re not, like, in a Mexican cartel or something, right?”

Chey laughed again. “No! Normally my stuff is in New York City, actually, it’s usually local around there. I’ve been to New Jersey a handful of times, Connecticut once, a couple trips to Chicago. But this delivery’s been crazy. I think it was just too much and too pure to risk shoving in the mail? The guy I brought it to weighed it like, six times in front of me before agreeing on paying up. Glaring at me too, like...dude, I wasn’t spending my trip here shaving lines off your fuckin’ bricks of booger sugar.” Chey’s audible amusement made Anthony feel at ease, and he was curious to know more.

It was clearly the wrong way of thinking, but with the long black hair and a self-done lip ring, train-hopping and drug-running, casually laughing about dodging cops or being fixed with an accusatory glare…everything about Chey seemed to come across as cool—other than maybe his goofy smile—and Anthony was undeniably impressed.

“You train-hopped all the way here from New York with a whole bunch of cocaine?” he asked, somewhat awed, “Weren’t you afraid of getting caught?”

“God, I would’ve been,” Chey said, “but no, I had a Greyhound ticket out here. I was supposed to buy one to get back, too, but why waste the cash? I’ll be a bit late returning, but the guy already wired off the actual payment, so I don’t think my boss will mind.” He shrugged easily and smiled at Anthony. “Besides, I get to make a new friend this way. Worth it.”

Anthony was too stunned at having been deemed “worth it” to even begin to formulate a reply, but luckily Chey wasn’t the type to let silence hang; he changed the subject and continued talking, and they were still deep in conversation when the sun finally sank below the horizon and night fell around them.

Through the darkness, the two boys kept watch of the dimly lit railyard—and it wasn’t that long after nightfall that a yellow train came pulling in, spurring Chey into excitedly exclaiming “That’s us! That’s our train!” over the creaking rumble of the cars as the train slowly ground to a halt.

“You’re sure?” Anthony asked uncertainly; it looked like any other freight train to him.

“It’s yellow—Union Pacific,” Chey said, pointing. “The crest is up front so you can’t see it, but it’s company-yellow and northbound. Since we’re fine whether it heads east from Cali or just keeps going up to Oregon, we’re all set with it.” He smiled and excitement danced in his eyes as he looked away from Anthony, back to their train. “We’ll wanna give the yard crew time to do their checks and run through,” he said, “So we should wait until the engine just barely starts up again, then get on before it actually starts moving. We’re gonna have to run a bit. You up for it?” Chey flashed Anthony his signature grin and Anthony smiled back with a determined nod.

“Yeah.”

In the safety of the scrub-brush shadows, he and Chey crept closer to the yard, back to their initial meeting place, and sat together again on the pile of scrap lumber. Anxiety and anticipation were waging war in Anthony’s chest, strangling and strengthening him in equal measure as he waited alongside Chey, both of them silent, focused. It could have been twenty minutes, or fifty, or the blink of an eye—but finally the yellow engine rumbled to life again and Chey grabbed Anthony’s hand, pulled him into a standing position with a smile of pure exhilaration and a “Let’s go!”

They slipped through a hole in the rusty barrier fence, then ran low in the darkness to their train—dodging patches of light and barely avoiding tripping over the many train tracks. The train and ground alike vibrated as they grew close, but Chey seemed undaunted and pulled Anthony along as he jogged down the train, scanning the cars. Before Anthony could ask what he was looking for, though, Chey found it; one of the boxcars had been left just ajar, and with a triumphant noise, Chey managed to shove it open. He showed no hesitation as he threw his backpack off his shoulder and into the boxcar, then clambered in after it. In the heartbeat where Anthony hesitated, Chey turned around and extended his hand, smiling, as always.

“Empty!” he beamed, “Not even cargo—it’s all ours! C’mon, Anthony!”

His confidence and easy smile were reassuring, and Anthony took his hand as he, too, climbed up into the boxcar.

“Anthony,” Chey half-laughed, shaking his head as he settled back on his heels, “I can’t with that. What’s your middle name?”

“...Arland,” Anthony said with distaste, the middle name he shared with his father bitter on his tongue, “Anthony Arland Keystone.”

“Hm…” Chey tilted his head back thoughtfully. “I don’t really see you as an ‘Arland’ either. What about ‘Ari’? Ari’s a fun name.”

Anthony gave a jerky head-shake.

“I definitely don’t want you calling me ‘Arland’,” he said, unable to keep his lip from curling, “It’s my dad’s middle name, too. My granddad’s first. Way too much fuckin’ family history.” Anthony sighed out his hesitation, then shrugged uncomfortably. “You can try out ‘Ari.’ But I don’t think it’s me.”

Chey nodded, looking thoughtful. “That’s fair,” he said, “I can’t see it sticking if it’s built off of a name you hate, but we need a placeholder ‘til we figure out your real name. It’ll do.”

Anthony quirked an eyebrow. “My real name…? Anthony is my real name,” he said.

“Is it though?” Chey asked, tilting his head, “Like, is it actually? I mean…my legal name is Kaspar, right? But that’s not my real name.”

Wrong-footed by the question, Anthony hesitated, considering Chey’s words. If he was totally honest with himself, he didn’t really identify with his name. He’d heard it too often in his father’s voice, threatening and angry. When his mother had said it, it had so frequently been in a tone of fear or apology. In his brother’s voice or handwriting, he could believe his name to be his—but every letter Hunter had written him was in a house Anthony had no intention of returning to, and he knew he’d never hear his brother’s voice again, no matter the name he used.

“...I dunno,” he finally said, feeling vulnerable.

Chey just smiled reassuringly at him.

“We’ll figure it out, don’t worry,” he said earnestly, “It’ll be easier once we get moving, I bet. New start. New name. New life.”

Anthony nodded and let the quiet hang for a few moments.

“Is that how it worked for you?” he asked, finally, “Why ‘Cheyenne’? Why ‘Chey’? Why not ‘Kaspar’?”

Chey rolled his shoulders and glanced away before answering.

“‘Kaspar’ just…stopped being me,” he said, his hand having subconsciously risen to the scar on his throat. “As for Cheyenne...I mean, that was easy enough. It’s just my middle name: Kaspar Cheyenne Reykjavík.”

“Bless you,” Anthony said, a small smile playing on his lips.

There was a beat where Chey looked at him almost incredulously, then cracked up into a reassuring comeback of that contagious laughter. When he caught his breath, his hand didn’t find his scar again and his eyes stayed clear and focused.

“Okay,” he half-laughed, “What was I saying? Right, my name, yeah—‘Kaspar’ just wasn’t me. It feels too sharp, somehow? Too sharp and...boxy? I dunno, it just...it seems unfriendly or something.” He paused and shrugged. “‘Kas’ is okay? But still…‘Cheyenne’ is softer, it feels like. Smoother? It just feels more like me. I got Chey from there, like I said before, and I like Chey because it’s easy—short and snappy, right?—and it’s friendly, I think. It’s like ‘Hey!’, and you kinda have to smile when you say it, ya know? That’s what I want, really, to make people smile more.” Chey concluded his sentence with another shrug and a smile of his own.

Anthony felt struck somewhat dumb; Chey was again giving off the feeling of being somewhat magical, because who on earth tailors their own name to try and make people smile? He was saved from stuttering a response by the train suddenly lurching forward, and with a loud grinding noise, beginning to move. Chey’s eyes still seemed bright even as they pulled away from the dim lighting of the freight yard.

“Here we go, Ari,” he said, “Your new start. Let’s find that name.”

It was freedom beyond freedom, no—freedom beyond imagination, at least as far as Anthony was concerned. Trains were fast and loud and the wind whipped his and Chey’s hair into wild messes, and their whoops of exhilaration were all but lost in the rattle of the tracks. It was a dream to watch the landscape fall into the distance, to watch mile after mile take its place between him and his father, between him and his past. And Chey—Chey was indescribable. Anthony hadn’t had friends before; he’d lost any semblance when he was pulled from public school to hide the bruises five years ago. All he’d had was Hunter, and when he’d lost his brother in May, he’d found himself painfully alone. Until Chey.

Chey seemed all but incapable of doing things in halves, and he skipped being “acquaintances” entirely; it seemed that Anthony had gone straight from “stranger” to “close friend” the moment he’d caught that water bottle, and the pair fell into step as if they’d known one another for years. Passing hot, monotonous hours on the rails or waiting for the next train out of Modesto (which had turned out to be only as far as their first train was going) left them with nothing else to do but bond, and they quickly found themselves sharing stories, and water bottles, and the single plastic spoon Chey had with him. As they headed eastward to the California border, Anthony ended up pouring out his heart and his childhood and the loss of his brother to him—because everything about his life involved Hunter and everything about leaving that life behind led back to Hunter’s death.

Chey cradled the dog-tags in his palms like something sacred when shown them, and murmured a kind, unprompted prayer into his cupped hands.

“...Are you religious?” Anthony asked afterwards, touched by the recitation and its reverent tone, even if to him it seemed likely to reach only an empty sky. Chey gave a small, self-conscious smile that appeared to waver.

“I dunno,” he said. “But with how you talk about him I figured he deserves the rest and light. Might as well try, right?”

Anthony made note of the present-tense and swallowed hard, fighting the burn at the edges of his eyes.

“Yeah,” he said thickly. “Yeah, he does. Thank you.”

He and Chey couldn’t avoid closeness, emotional or physical, sharing train cars. They slept side-by-side and used the lid off a can of Chef Boyardee to scrape the year and their initials into the paint of the boxcar they were meant to cross out of Cali in, beneath a faded drawing of a sun that had been left by some other vagabond in seasons past. It seemed an appropriate way to usher in a new dawn.

By the time their train pulled into Truckee—though it was more like lurched; it had started sputtering to spasmodic stops as they strained up into the hills—Chey and Anthony had been on the road for a couple hot and hardening summer days, which included their sweltering layover in Modesto: Anthony was pretty sure it was only because of the thick layer of dirt he’d accumulated that he wasn’t sweat-stinking Chey right off the train. He felt gross. But they’d made it into the mountains, where there were creeks and rivers and maybe even rain.

The world seemed greener than Anthony could have believed possible, and the Truckee River beckoned like nothing else: Pristine-looking and playful as it jumped over rocks and tumbled beneath bridges. Though it was far cooler in the mountains—hell, the early morning had been cold enough for him and Chey to need to huddle for warmth—now the midday summer sun and the dirt on his skin drew Anthony to the water beside the railyard.

“C’mon, we’re grimy as shit,” he laughed, tugging Chey by the arm, “And I wanna try and get the blood outta my shirt. Oh man, I bet it’s gonna be ice cold.”

They’d only known one another for a couple days; less than half a week, but that amount of time was enough for Anthony to feel Chey’s sudden quiet as strange. A heartbeat passed before Chey managed a laugh and a stiff shrug.

“Ya know, I think I'll wait ‘til we get to Nevada and I really need it. Don’t take your time though, I dunno how long our train’s stopping here, it shouldn’t be: We’re freight, not passenger,” he said, rubbing his hand to the back of his neck. He eyed the water warily while Anthony waded in—and instantly understood Chey’s reluctance. His legs immediately ached with cold and despite only being up to his calves, anticipating splashing himself clean brought a preemptive chatter to Anthony’s teeth. He let out a shrill whoop at the cold as he stripped off his shirt and waded deeper into the water to clean it, while still self-consciously trying to keep his scarred back angled away from Chey’s line of sight.

Chey didn’t seem to be paying too close attention anyway, though; he stood on the bank with his eyes on the water, looking nearly as cold as Anthony felt; his arms crossed tightly over his chest, his feet together. He glanced up and shot Anthony a look that might have been pity or amusement—or a grimaced mixture of the two: His lips were pressed thin but tilted into a lopsided smile, that when paired with his cinched-together eyebrows made him look like he was failing to simper. Anthony laughed again as he shivered and scrubbed at the bloodstain in his shirt.

“Yeah, okay, so it’s freezing and you made the right call. Wanna brag about it?”

Chey shook his head and took a step back from the riverbank.

“Nah. Just hurry up before you catch a cold or something.”

Anthony’s shirt stayed stubbornly bloodstained even as his fingers went numb, and eventually he was forced to admit defeat. He wrung it out and used it to sponge himself off, shivering heavily by the time he was done. It clung icily to his skin when he tugged it back over his head and rejoined Chey.

Back by the rails, they found potential workers—though most looked like simple gawkers or what Chey had called railfans—congregating on the hard-packed earth beside the tracks; so the two of them hid in some nearby shrubs, feeling like little kids, and listened to a couple of the men arguing at one another:

“Listen, they just don’t have the capacity for maint work here, they don’t even have station staff for the Zephyr. We’ve made it this far, I think we can manage to hobble down to Reno,” one man said; “It’ll take longer than it should but they can swap out our locomotive and we won’t be blocking the line here waiting for responders.”

“‘I think,’ he says!” his larger, bearded conversational partner exclaimed, throwing up his hands; “Some conductor you are! Fine, but if it all goes to hell and you catch us careening out of the mountains like that damn horse movie, don’t come crying to my funeral, Frank!”

“If that happens I think I’d have to miss it...What horse movie?” Frank’s quirked eyebrow was just about audible.

“My daughter watches the shit out of it. They go over a waterfall too. Don’t ask me any more questions, I’m sick to death of the thing. Just clear the rubbernecks off so we can get set for Nevada and radio the signaller that we’re delayed. I’m re-checking the air brakes my damn self.”

“...Sure, you got it,” Frank sighed, before turning around and starting towards the curious onlookers, clapping and waving as if shooing off stray cats; “ALRIGHT YOU ALL, BUSTER KEATON AIN’T HERE, GET ON BACK INSIDE, WE’RE FINE.”

As the crowd scuttled back towards the passenger station, Chey and Anarchy scrambled for their boxcar, half-laughing and slightly exhilarated by the danger of their apparently-broken locomotive; both of them grinning even as they crossed their fingers that their particular train car wouldn’t end up one of the ones uncoupled and careening out of the mountains like that damn horse movie, Frank.

The temperature dropped with the onset of evening, and as their protesting train departed from the chilly mountain town, Not-Frank’s brake-checking having taken quite some time, Chey and Anarchy curled close to one another in the most insulated corner of the boxcar they found—huddled beneath a fleece jacket Chey refused to wear and insisted on draping over the both of them as a makeshift blanket. The trundling train was loud but they both were tired enough to drift off, with Chey’s final sleepy mumble that they were on their way to Reno, now, and it would be warmer there, for sure.

It seemed like he’d only just slipped into sleep when Anthony was startled awake by the wrenching sound of someone choking for air. It was an awful, soul-rattling noise, and Anthony ripped himself awake, his heart hammering with the memories of his father’s hands around his mother’s neck. Hunter had leapt in and pried him off and it had never happened again but the sound was there, burned in his memory, echoing in his ears. Anthony whipped around, searching for the source, and found Chey beside him, in the throes of some awful nightmare. Another throttled gasp left him and he weakly clawed at the air; only his normalized breathing between gasps lending Anthony any reassurance that he wasn’t actually asphyxiating.

“Chey! Wake up,” Anthony said, shaking Chey’s shoulder. Chey jolted awake at his touch and seized, terrified, onto Anthony’s shirt, still gasping raggedly.

“Hey, man, whoa. It's a nightmare. You alright?” Anthony asked, awkwardly rubbing his friend’s shoulder.

“She’d try and drown us,” Chey choked out, wild-eyed, immediately interrupting himself with a breathless, terrified, child’s-voice please-please-please-no; a desperate appeal clearly meant for someone other than Anthony. Chey clung to the front of his t-shirt, fingers knotted tightly into the fabric, his breaths coming short and fast enough to outpace the clickclickclick of train wheels.

Anthony furtively glanced around the boxcar, at a loss for what to do or say and hoping for some distraction to appear outside for him to call Chey’s attention to. Instead, Chey suddenly fell silent; his eyes wide but distant; his swift, shallow breaths abruptly held. He started to shake.

“Dude, hey, snap out of it,” Anthony said anxiously, giving Chey’s arm a squeeze; “Chey!”

Chey startled and his eyes seemed to refocus on Anthony, though they stayed terrified. He quickly shook his head and his already-vicelike grip on Anthony's shirt somehow tightened. He opened his mouth but couldn't seem to speak. Some frail, bird-like sound of distress escaped his lips and then a rush of words; I’m-not-I’m-not-I’m-not—

“She’d say the Devil was in us but He isn’t, I swear!” he burst out, suddenly keening; “I don’t need to go in the water, please, I don’t I don’t I don’t—” He tried to cower but his fingers were still latched onto Anthony’s shirt and he looked too alone to not need the hand on his arm. Anthony tried to reign in his own panic at his new friend apparently losing his mind and rubbed Chey’s arm again.

“We’re on a train, man. No one...no one’s...putting you in water? The Devil...isn’t...around?” Anthony cringed at his own ineptitude but Chey leaned into the gentle touch and the reassurance, however clumsily delivered.

“If she finds me she’ll think He is, oh God, please, don’t let her find me…” Chey whimpered, pressing his head to Anthony’s sternum. He seemed far, far younger than thirteen, and as he directionlessly whisper-pleaded don’t-hit-me don’t-hit-me don’t-hit-me under his breath, Anthony frowned with sudden understanding.

“You’re talking about your foster mom, aren’t you?” he said. “You ran, you told me the other day. Me too though, right? So...we’re on the run together; partners in crime and all that. It’s okay. I’ve got your back.” He moved his hand from Chey’s arm to rub his back, and Chey seized him around the middle, the fear fueling the hug so potent Anthony could’ve choked on it. Furrowing his brow, he wrapped both arms protectively around his shaking friend and decided he abjectly hated the person who had caused Chey to wake up so terrified and so far from himself.

A few minutes passed before Anthony noticed a change in Chey’s posture: Some of the tension left his shoulders; his arms seemed to relax. Anthony released him so he could pull back and push himself up, which he did, blinking blearily at Anthony’s chest, where his face had just been buried.

“Are you ok?” Anthony asked.

“...Yeah, yeah, of course…” Chey sounded a lot more like himself, if a little confused. “Are you?”

Anthony quirked an eyebrow. “...Yeah, of course.”

Chey nodded, looking sleepily at Anthony's chest another couple moments before shrugging a shoulder— having apparently reached a conclusion—and nuzzling back into his shirt like a puppy.

“Are we to Reno yet?” he mumbled.

Anthony peered out the cracked boxcar door, beyond which the lights of suburban sprawl twinkled. The air coming in from outside seemed warmer; the ground seemed flatter.

“Almost, I think,” Anthony said.

“Mmn. Wake me up when we get there.”

Their train creaked into Reno at a snail’s speed, lurching and limping the last few miles to the yard, which Chey and Anthony snuck out of with sleep-fumbled feet and heavy eyelids, clinging to one another’s wrists to keep from getting separated in the disorganized dark. They flattened down some tall grass just beyond the yard’s rusted chain link fence and fell asleep together under the shield of scraggly vegetation and each other’s company.

Come daylight, Chey was up before Anthony was, spirited and bouncing on the balls of his feet before Anthony had even rubbed the sleep from his eyes.

“Mmn. You’re feeling better, then? Anthony asked, stretching; “Last night you were really freaked out.”

Chey stilled and cocked his head to the side, dog-like. “Huh?”

Anthony raised an eyebrow at the apparent confusion. “Your...you were talking about your foster home, like, and the Devil or something—”

“Oh! Nnh, I don't wanna think about it!” Chey said swiftly; his hands jumped to the sides of his head for the briefest moment before he snatched them away—and suddenly looked a lot more Normal. “I’m good, okay?” he grinned, just like he did on the log pile back in Fresno; “I’m okay now.”

Anthony wondered how someone’s eyes could look so clear even as they ducked back into hiding. Vaguely, he wondered if Chey even knew he was.

Over the next few days Anthony noticed Chey’s strange behavior in a couple more nightmares: The raw, debilitating fear and the denial of talking about it when it was over; the confusion Chey seemed to have when coming out of the panic, like he was surprised to find himself in such a state and struggled to hang on to the whys of it all once his eyes were no longer clouded by his past.

The August nights refused to get truly cold down in the valley, but they were cool and comfortable and easy, and lended themselves well to sharing stories and the weight of Chey’s head on Anthony’s chest—which seemed to help with the nightmares and failed to feel awkward or unfamiliar despite how short a time they’d known one another.

The days were a different story in terms of comfort. Nevada was HOT, hot like nothing else: Despite the shade of the boxcar they both had to peel most of their clothes off as they snaked through the state and sweat still beaded off of them like condensation on poolside soda cans. It made Anthony feel sick and vulnerable, that first time, to pull his t-shirt over his head and finally expose the scarring that marred his back, unable to hide it all when they were stuck in close quarters together. Chey didn’t gasp with horror or shy away, though—rather, he gently ran his fingers over the scars that criss-crossed Anthony's spine, fixed his eyes on Anthony’s own, and determinedly said, “Never again.”

When they finally pulled into the Union Pacific yard in Ogden, Utah, Anthony was quick to note the creek beside it; the opportunity to rinse off the sweltering desert days and to not walk into Walmart to buy water looking—or smelling—quite as homeless as they were. Chey hung back just as he had in Truckee, and having heard his nighttime pleas of ‘stop, you’re drowning him!’ and ‘please, no, I don’t need to go in the water,’ Anthony wasn’t surprised by the reticence, but still tried to persuade Chey that just washing off would be a good idea.

Chey stood on the bank and watched Anthony wade in, drawing fast, shallow breaths that tugged at Anthony’s heart.

“I can't. I really can’t,” Chey said, shaking his head. Anthony looked back at him and frowned.

“No, look...it’s only up to my knees here, see? And there’s, like...no current. You’re taller than me, too, it’ll be fine.”

Chey looked ill and shook his head again, harder.

“Look, here...hold onto me.” Anthony reached out his hand. “I’ll make sure you don’t dunk yourself or anything. Even if you spaz out and fall over, I’ll catch you. I won’t let your head go under. I promise.”

For a few moments Anthony’s hand just hung in the air beside his invitation, suspended before Chey’s fearful eyes as he assessed them. Then, slowly, he reached out and took Anthony’s hand. He held onto it without moving for a couple more heartbeats, as if ascertaining it’s stability, before taking his first timid step into the water. He shivered despite it being lukewarm in the shallows.

His grip on Anthony’s hand was threatening to cut off circulation to his fingers by the time Chey got the few steps close enough to him to cling to his upper arm instead, sucking at the air as though finishing up a marathon.

Anthony worried about his wide eyes going glazed the way they would when he truly lost it, so he tried to keep him talking; asking questions about where to from here and do you know anything about Utah and the salt lake was really pretty, wasn’t it? Aside from being made of water, of course, he hastily added, and Chey managed a frail laugh, if one pitched by fear.

Anthony walked him in circles in the shallows for a bit, hoping that once the newness of being in water had subsided, the fear would, too. Chey did seem to ease up slightly, but he clutched Anthony’s arm with both hands the whole time, and his grip didn’t loosen. The first step Anthony took into knee-deep water brought forth a heart-wrenching near-sob sound from Chey, who wouldn’t step closer to him but held fast to his arm and begged him back towards shore with the fear in his eyes. Anthony, compelled to retreat from the deeper water, realized he and Chey simply were not going to be able to take a quick swim.

“So, we’re not gonna go in any farther,” Anthony said aloud.

“We’re not?” There seemed to be an undercurrent of relief to Chey’s voice.

“Nah. There might be...Sharks,” Anthony said; the fact that Chey laughed again was reassuring. “We can just scrub off here where it’s easy to stand; it’ll do.”

Sheer relief seemed enough comfort to allow Chey to let go of Anthony’s arm so they both could wet their shirts and scrub themselves down with them, but though Chey managed most of his torso with relative ease, he ran into obvious trouble with his neck and hair. He couldn’t stomach dipping his head in the water like Anthony had done, but even without forcing himself through that, he was still left whimpering slightly every time he brought another cupped handful of water up to tip over his head or pressed his sodden t-shirt to the back of his neck.

Turning to him, concerned, Anthony was reminded abruptly of himself—some memory rooted four or five years in the past: He’d only just been pulled out of school and his father had shown no restraint, leaving his back sticky with blood, then told him to go wash himself up. The showerhead would have been agonizing, so he’d opted to try and sponge himself off—but it had hurt so badly: Both to touch the sponge to the wounds on his back and the twisting he needed to do to try and reach. He’d sat, whimpering, on the edge of the tub when Hunter had appeared in the doorway, a bruise blooming across his own cheek—and gently taken the sponge from Anthony’s hand and cleaned the blood from his back.

Anthony blinked the recollection away and took a step towards Chey, who’d screwed his eyes shut and murmured some frail, inaudible plea to no-one in particular as he shakily pressed his wet t-shirt to the nape of his neck.

“Hey, it’s okay, Chey, here,” Anthony said softly, reaching out; “Let me.”

Chey’s eyes were deerlike and fearful when he reopened them, and he froze in place for a few heartbeats, just looking at Anthony like he had before. Anthony offered him a small, reassuring nod.

“I didn’t let you fall in before, right? You can trust me,” he said. “I just wanna help, since it’s hard.”

Another couple moments of hesitation passed before Chey slowly—searching Anthony’s eyes the whole time—put his shirt into Anthony’s proffered hand. Chey swallowed hard and nodded, dry-eyed but somehow still reading as tearful.

“Thanks. Don’t worry,” Anthony said. “I’ve got you, dude.”

Chey ended up being able to let Anthony rinse the dirt from behind his ears, though a shudder ran through him a couple times when there was too much water brought up in the cloth and it ran in rivulets down his back. Anthony realized it was best just to have the shirt damp but not wet, though that became unavoidable when it came to Chey’s hair, which Anthony awkwardly started to detangle by hand before Chey’s shivering and his own discomfort made him call a half-done job good enough. If need be, they could buy or swipe some dry shampoo, anyway.

“...How do you normally get clean?” Anthony asked afterwards, as they sat slowly drying in the shade of the trees, their eyes on the yard.

“...Shower. Rain. Sometimes if I don't have any choice I just...force myself through it,” Chey said. He sounded to be on a razor's edge between lucidity and regression. “It’s just worse when it’s deep or it can’t be fast or I have to put the water on myself…feels like torture. With a shower I can just go in and out and pretend it’s rain.”

“...Do you know right now why it freaks you out so bad?” Anthony asked, even though he wasn’t certain how good an idea it was; if it might trigger another episode. Chey just gave a slow, solemn nod, though.

“Yeah, ish, but it doesn’t stick. Or the details don’t; I know they don’t. People think I’m weird ‘cause of it, forgetting…don't know why I always do.”

“But you remember that you forget?”

Chey shook his head. “Not really...parts of it just...get dark again. But I know they weren’t before, or that they’re there, somewhere, but not right then.” He looked puzzled and brought his hands up to the sides of his head; a familiar gesture.

“I already know some of the details have gone away again...don’t know how I know...just know I used to know more. Know know know know…” He dropped his hands and gave Anthony a grin; “Funny how if you say a word a lot it stops sounding like one, huh?”

Anthony blinked, but returned the smile; deciding he didn’t think Chey was weird at all for forgetting, and that judging by what he’d surmised about Chey’s history, forgetting as much as possible was likely the best course of action.

“Yeah, it’s weird. That’s why I try not to talk too much, in case I wear all my words out of being words,” Anthony joked. “Probably more of a problem for you.”

Chey wrinkled his nose; his eyes were clear and bright again. “Whaaat? You saying I talk too much, Ari?”

“Saying you talk a lot. Dunno where you’re getting ‘too much’ from.” Anthony shrugged, glad to see Chey’s eyes light up further. “Hey, look, is that us?”

A train was pulling into the loading yard, its yellow lead locomotive bright as a beacon. Chey beamed at it and grabbed Anthony’s hand, jumping to his feet.

“I think so! Let’s head out!”

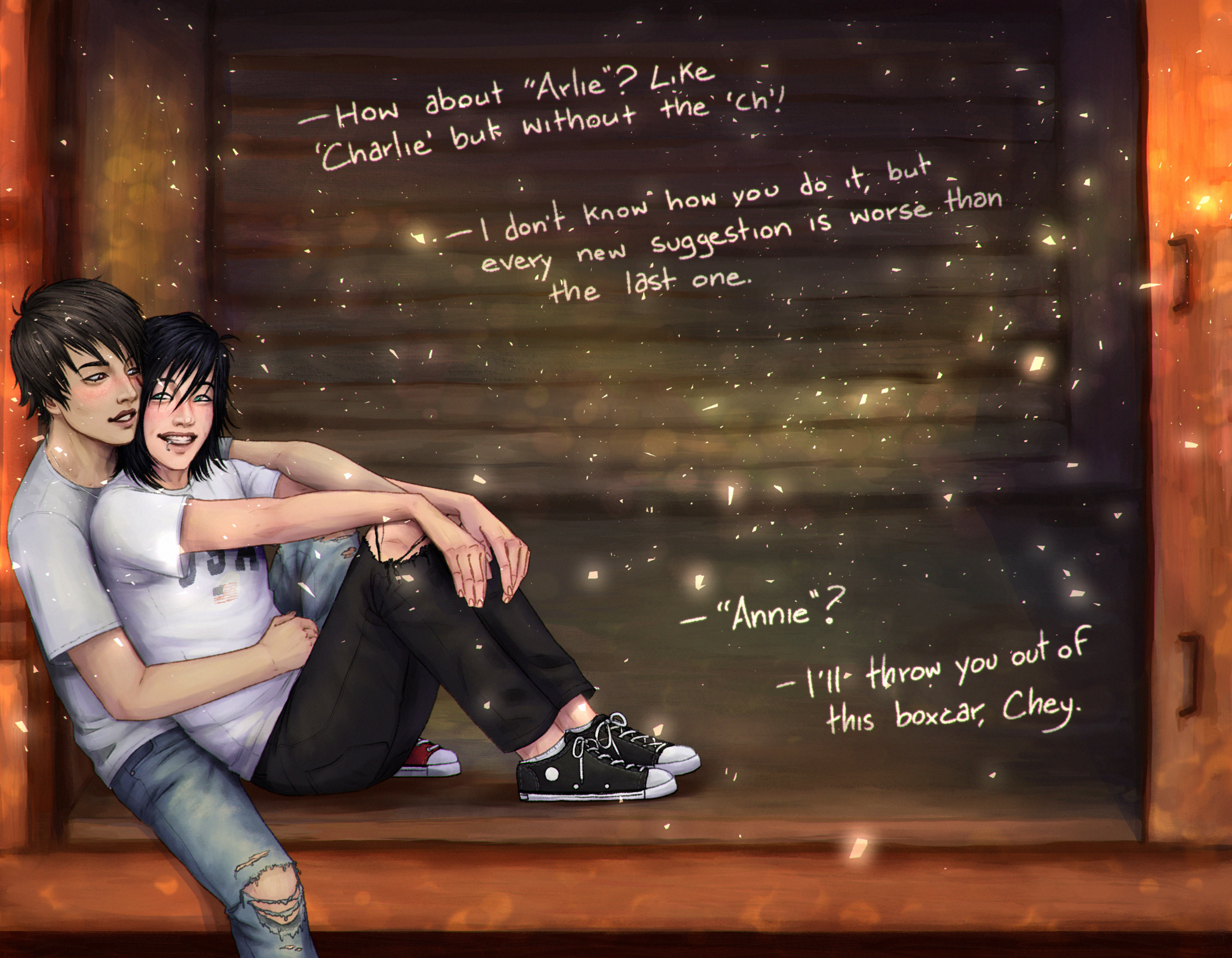

Their new train wound northeast, away from the desert heat and all the memories therein; welcome and stabilizing distance. As prairie grass and farmland replaced dry earth and salt-pans, Chey set about trying out an endless stream of new nicknames for Anthony (“Because Anthony’s a dweeb name, Ari,” he explained) and Anthony shot them all down with increasingly exaggerated looks of disdain that made Chey laugh—which was, of course, the goal. Something between them felt fated, destined, safe, and even through the chaos of hopping off and catching out and hiding from railyard Bulls, there was an unspoken sense of stability in doing it all together.

They’d switched trains in Wyoming in the early morning a week into their journey, then haltingly napped away the daybreak hours, until the sun truly rose and burned away the dawn mist. It was just barely mid-morning when Chey rolled over in the boxcar, lazy and cat-like in how he stretched, then propped his chin on Anthony’s chest with a grin.

“You’re dead set against Ari, then?” he asked, returning to the days-long game they played together in the hunt for Anthony’s “real” name.

“Look, if it was between Ari and Kiki, I’d pick Ari, but I really don’t want to go by Ari,” Anthony said, crossing his arms behind his head and grimacing at the nicknames, “I’m okay with just ‘Key.’ But I still don’t understand what’s wrong with ‘Anthony’.”

“It’s just not you! And Anthony’s a dweeb name, I’ve told you this.”

“So? ‘Tony’.”

“In New York? Everyone would think you were some mafia-wannabe asshole. No. Just give me a bit longer,” Chey said, rolling over in place so that his chin was no longer digging into his friend’s sternum, but continuing to use him as a human pillow as he mumbled variations of Anthony’s name to himself on repeat.

“Anthony Arland Keystone. Anthony Arland Keystone…Anthony. An-Tony. Arland, Ari. Ari-Key…Ar…Key…hey, wait, holy shit!” Chey suddenly sat bolt upright and twisted to look at his friend, triumphant excitement plain on his face and clear in his voice as he exclaimed, “An-Ar-Key! Anarchy!”

“‘Anarchy’?” Anthony repeated skeptically, with a half-snort, “I dunno, Chey…”

“C’mon dude, it’s badass,” Chey said, too excited to sound pleading, and unable to make a proper attempt at puppy-dog eyes due to his smile.

“I don’t know that I can live up to it!” Anthony said, “Isn’t it...ya know...a bit edgy? If you’re worried about what people would think if I introduced myself as ‘Tony’...”

“Fine,” Chey said with a laugh, “Everyone else we meet, you can introduce yourself as ‘Anthony Dweeblord Keystone.’ But I’m calling you Anarchy. ‘Key for short, still, since you’re okay with that one.” He lay back down with an air of finality that made Anarchy want to laugh.

“‘Anarchy…’” he said quietly, testing his new name out, “...Alright then.”

The train snaked its way through Wyoming and Chey used Anarchy’s new name so often that it could have been a punctuation mark. The pair left Laramie in the dust behind them and when they got to Cheyenne, Chey used the location as an excuse for them to again make their mark—not their initials this time, but their names. Another can lid, another layer of paint scraped away in another boxcar:

Cheyenne & Anarchy.

And though it was set in painted wood and not in stone, it might as well have been—there was a sense of permanence in Chey’s eyes when he turned and asked what Anarchy thought of his handiwork, and there was no hesitation in Anarchy’s tone when he responded, “Can you do the little circle around the A?”

By the time they reached Illinois, Anarchy responded to his name as readily as though he’d never known one before it, and with every passing day seemed to strive towards its meaning; towards living as a revolution. The Chicago yards were big, bright, and busy; well-lit even after dark, crowded with crew and Bulls—but with half the country between himself and his father, defiant exhilaration had replaced fear in Anarchy’s eyes.

He and Chey dodged flashlights and sight lines as they ran low and breathless through the CSX railyard, adrenaline pumping and hearts racing as they ducked through the shadows and avoided tripping on railroad tracks or ties. The tracks were innumerable and the cars seemed endless, but he and Chey eventually found their train, found their car. It had, fittingly enough, been graffitied sometime in the past with the Ⓐ. And there in that train car, with his new name and Chey by his side, Anarchy felt nothing less than invincible—so when the engine came to life and the train picked up speed as it pulled out of the crowded freight yard, he leaned out of their train car and whooped his triumph into the night air, not caring if the Bulls heard; the train was moving too fast for them to do anything now. He beamed at Chey, and Chey grinned back.

They’d left Ashtabula and were trundling their way through the forested northwest corner of Pennsylvania when around noon one day, Chey finally said, “So…I’ve been thinking.”

“Proud of you,” Anarchy grinned at him, “But don’t strain yourself.”

Chey gave an amused snort and rolled his eyes.

“Shut your ass. Anyway—you don’t really have a plan for when we get to New York City, right? Like…you said a while back you don’t know anyone there.”

Anarchy frowned and leaned back against the wall of the boxcar, watching the trees pass by outside.

“No,” he said finally, “I guess I don’t.” He’d somehow forgotten along the way that Chey had his own life back in New York, had his own job, had a purpose and things to do that Anarchy wasn’t involved in. The realization was so painful that it took him a second to break free from his emotions and register what Chey said next;

“Yeah, so, I was thinking—if you wanted—I could probably talk the Boss into hiring you?” Chey said, looking somewhat bashful as Anarchy stared at him, agape, and seemed to get concerned that that speechlessness was borne out of offense.

“I know it’s not, like, a noble line of work or anything,” Chey said, “and I’ve told you it’s not glamorous. But I just—I thought, if you don’t have anything else—it’s an option? And...I’d really like to be able to stick with you.” He glanced away. “Only if you want.”

Relief flooded through Anarchy’s chest and a smile bloomed across his face—he wouldn’t lose Chey after all.

“‘Only if I want’?” he asked, almost laughing, his relief was so great, “That would be incredible! You’d do that? You really think he’d take me? Duh, I wanna stay with you!”

Chey was beaming back at him, somehow looking equally relieved.

“Of course he’ll take you!” Chey said, “I’ll vouch for you, for one, and besides—you train-hopped across the country with me and we didn’t come close to getting caught! If that doesn’t prove resourcefulness or whatever, nothing does. You’re incredible, he’ll see it.”

Anarchy flushed slightly at Chey’s words and couldn’t stop smiling, even though his cheeks were beginning to hurt.

“And we’ll stick together? It’s okay?” he asked, only somewhat anxiously.

“‘Key,” Chey laughed, “That’s kind of the whole reason I offered.” The corner of his mouth twitched slightly. “Is it too soon to say you’re my best friend?” he asked.

“I hope not,” Anarchy replied, “I don’t have any other friends, so…You’re mine by default.” He paused. “I don’t think anyone else could compete, anyway, though.”

At that, Chey (for once) couldn’t seem to form words to reply—so he settled for smiling as hard as ever and all but throwing himself into Anarchy’s arms to hug him. And there, at that point? The only concern in Anarchy’s mind was that eventually they’d need to switch trains, and he’d have to let go.

They reached their destination less than a week later. Anarchy was expecting the railyards in New York City to be even bigger and more crowded than those in Chicago, but he found himself to be wrong. They pulled into a rather small yard in the Bronx just barely before dawn, and through the cover of semi-darkness and the noise of the neighboring expressway, snuck easily out onto the streets.

“Follow me!” Chey said, turning to Anarchy in the yellow pool of light beneath a streetlamp and gesturing down the road. “We’ve got a ways to go today; we need to get to Brooklyn from here—but I wanna show you something first.”

Anarchy allowed Chey to guide him by the hand past several commercial garages and a row of building back-lots, when he realized he could see water through the small trees lining the road up ahead. They rounded the curving street and suddenly the view opened up, stopping Anarchy in his tracks. Dawnlight was beginning to brighten the edge of the sky, but the city buildings and bridges stayed illuminated in the half-dark, reflecting in the water like fairy lights.

Chey grinned at Anarchy and pointed at a dark, treed island midway between them and the city glow across the water.

“That’s North Brother Island,” Chey said, “There’s some disease thing that happened there, it’s totally abandoned. The river is the East River. The lights across from us—that’s Long Island. The bridge—” Chey pointed at the beautifully lit bridge that arched across the river in the distance, glowing like a greeting, “—that’s Hell Gate Bridge. Dumb name, I know. And we can’t see it from here, but along the river past Hell Gate…is Manhattan.”

He turned and beamed, his eyes glinting in the pink and gold of the advancing dawn.

“Welcome to New York City, Anarchy.”